An introduction to Eighteen Echoes by composer Justin Morell:

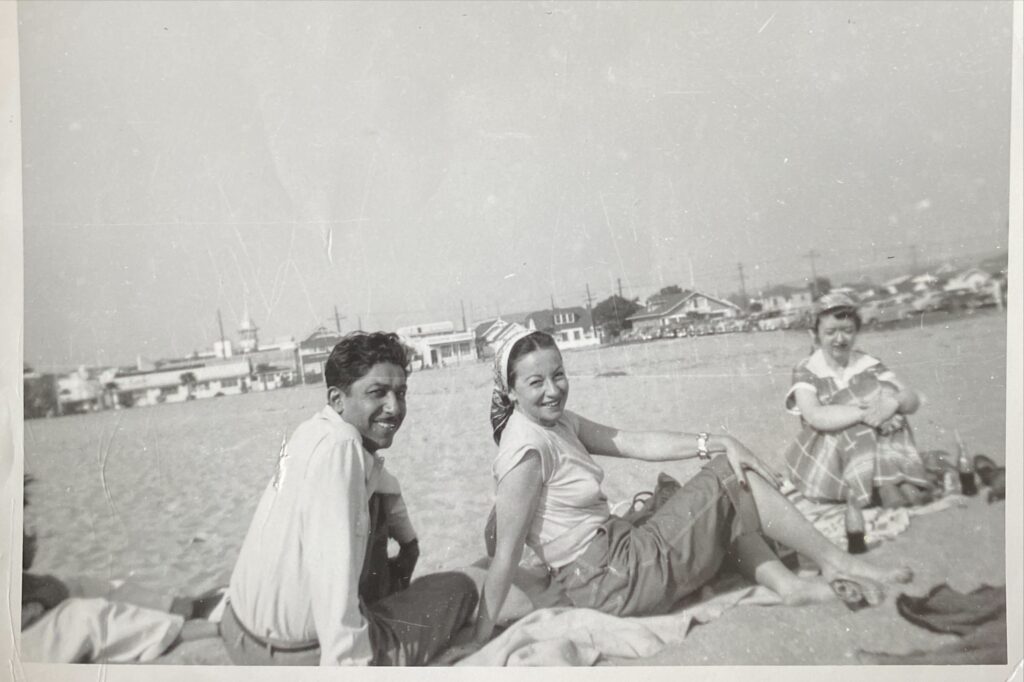

Over the course of several years, my grandfather, Cherokee composer and bandleader Carl T. Fischer (1912-1954), worked on a multi-movement orchestral suite called Reflections of an Indian Boy. The piece was nearly complete when he died at the young age of 41, and was later recorded and released on Columbia Records under the supervision of Paul Weston and Fischer’s longtime collaborator Frankie Laine. Though I have been aware since childhood of this “Indian Suite” as he originally called it, only recently have I had a renewed interest both in the music and the story behind its composition. Unlike some of my grandfather’s other very well-known works, this piece is quite obscure and rarely performed other than as incidental music for the play Tecumseh! that runs every summer at the Sugarloaf Mountain Amphitheater.

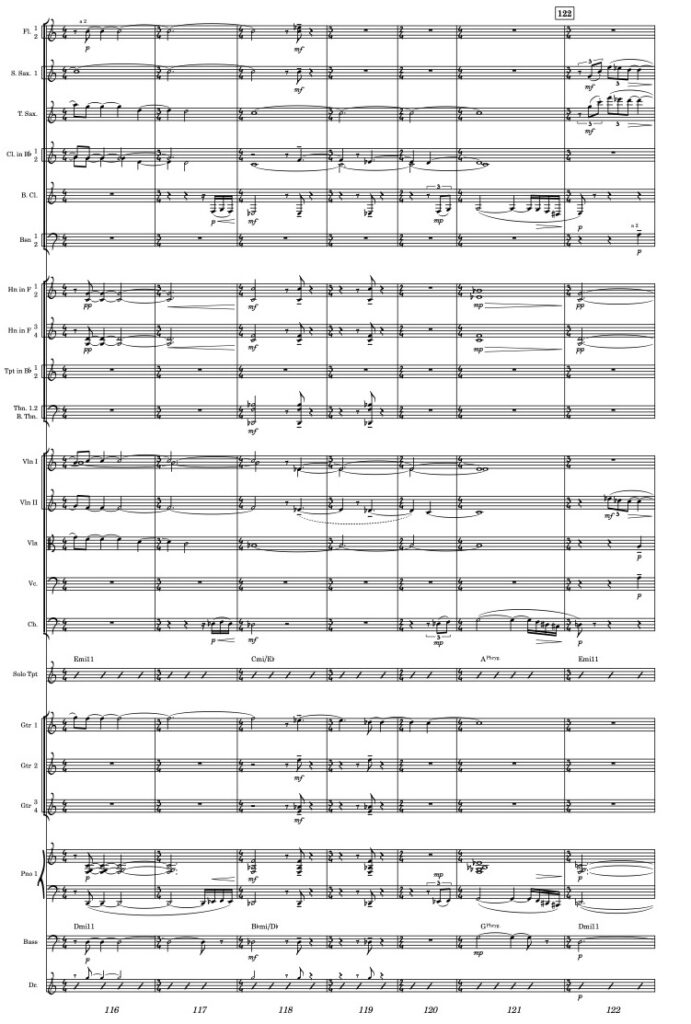

In 2021, I began studying Reflections in depth, getting to know especially the melodies and the spirit behind each movement. I transcribed the melodies and recognized some of the familiar shapes that occur in much of Fischer’s other music, as well as much of the popular music from his most active period of the 1930s and 40s. In each movement, I focused in on one or two very small motivic elements that were particularly unique and captured my interest. From there, I began constructing my own sketches for what I hoped would become a new multi-movement orchestral work.

At the same time that I was exploring my grandfather’s music, I was also becoming interested in learning about his family history and Cherokee heritage. Since he died at such a relatively young age—his younger of two daughters, my mother, was four years old at the time—much of his family history died with him, save for a very few letters and bits of memorabilia that were eventually passed down to my mother. Certainly during the first half of the twentieth century, being “Indian” meant living in a world of stereotype and bigotry, and so much of my family’s Cherokee culture was hidden. Thus, my childhood saw virtually none of it. As I explored Reflections, I became more curious to know where my grandfather came from and whether any of his Cherokee relatives remained.

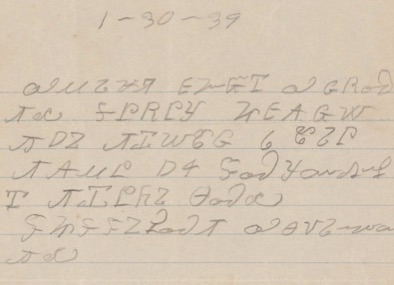

My search for family connections was mostly unsuccessful. However, my interest in Cherokee culture and people grew, and I therefore began learning about the history, the three tribal nations, and especially the language. I came across a collection of documents assembled by Jack F. and Anna G. Kilpatrick, now housed in the Beinecke Collection at Yale. These documents, mostly written in the Cherokee syllabary invented by Sequoia in the early nineteenth century, are small windows into the daily lives of Cherokee citizens. They include love letters, lists, legal documents, musings, and various bits of communication between parties, spanning from the 1800s into the middle of the twentieth century. While I cannot read the syllabary, some of the documents exist in partial translation, enough to give me a sense of their subject matter and tone.

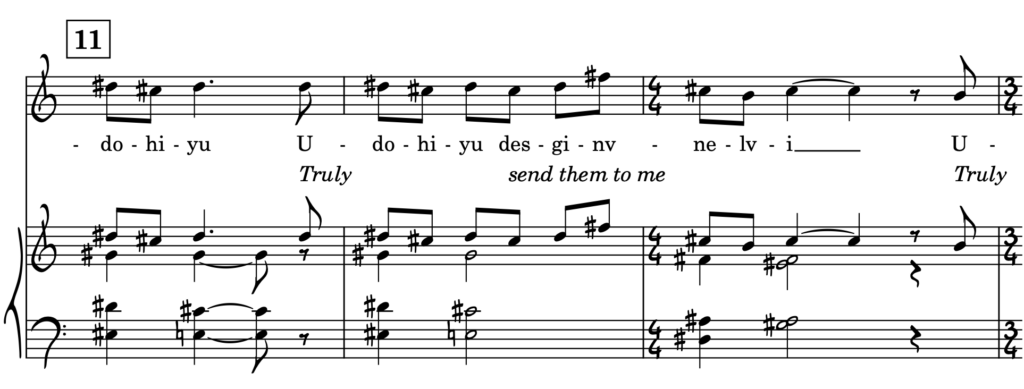

I became truly enamored with some of these brief writings. While none of them is written in poetry, their prose displays a poetic brevity and care with word choice. I imagined these writings could be adapted as song texts, and that those songs could serve as companion movements to the nine instrumental orchestral movements based on Reflections. From there, I began contacting academics within the small network of Cherokee scholars across the US asking for help with translation. I connected with Professor Sara Snyder-Hopkins at Western Carolina University, and after explaining the details of my project she expressed enthusiastic support and generously agreed to translate a small group of these documents.

It took about a year for Prof. Snyder-Hopkins and Tom Belt, a native Cherokee speaker with whom she often works, to provide me with complete translations of the nine texts I chose. As she sent them to me, piece by piece, I worked through sketching the basic outlines of each song. At the same time, I worked to complete the instrumental works that accompany them.

Each of the instrumental movements is composed for full orchestra, with a traditional jazz rhythm section (piano, bass, drum set), four electric and acoustic guitars, and a trumpet soloist. Each of the vocal movements is scored for choir with string orchestra, guitars, rhythm section, and occasional trumpet soloist. The completed work is approximately two hours long. The music ranges in style from classical to jazz, with some sections fully notated and others including improvisation. The musical language draws from Cherokee musical history only to the extent that it already exists in the melodies originally composed by my grandfather from which I have drawn small excerpts.

The vocal melodies and choir parts range in difficulty such that the movements can be performed by a choir mixed with both experienced and young singers. I have been in contact with two prominent Cherokee vocalists: opera singer Barbara McAlister, and director of the Cherokee Youth Choir Mary Kay Henderson. Both have agreed to help facilitate the participation of Cherokee vocalists on a recording of the piece. During the fall of 2023, the Lebanon Valley College Chamber Choir, under the direction of Dr. Kyle Zeuch, will be rehearsing and recording the vocal parts that will serve as the foundation upon which individual Cherokee voices will be layered. I have a complete digital mockup of the piece for the choir to follow. Having these vocals in place first will make it easier for other singers to learn the music not just by following the score but by listening. Prof. Snyder-Hopkins will be traveling to Pennsylvania to work with the choir on language pronunciation and phrasing.

As we continue to add voices to the existing mockup, I plan to assemble a live orchestra and rhythm section to record the remaining written parts in preparation for a commercial release. While the composition of the music takes by far the greatest amount of time, it is the recording and subsequent release of the album that necessitates significant funding. I estimate that the piece will call for an orchestra of approximately 70 musicians, plus a choir of 10-12 additional vocalists. I also expect additional expense to facilitate travel to Oklahoma and North Carolina to record Cherokee singers that are willing to participate. Finally, the recording will be paired with visuals, either live dance or animation by members of the Cherokee community.

The mission of this project is both personal and community-centered: this piece is about connecting with the family that I never had a chance to meet, and to learn about who they were and where they came from; and it is about celebrating Cherokee culture and language with an audience that may not know its complexity and beauty. I plan to include with the recording (and subsequent live performances of the piece) a guide to the texts, an introduction to the Cherokee syllabary, and through this web site a portal from which listeners can find further information about Cherokee language and culture.